Montreal Women’s Right to Housing: We’re Working on It, Are You?

Accessing Social and Community Housing

Organizations' wait lists are a testament to the lack of social and community housing in Montreal. Its scarcity increases crowding in interim housing and emergency shelters. In addition to the lack of available spaces, these groups have identified obstacles to accessing these limited spaces and sources of exclusion:

Organizations' wait lists are a testament to the lack of social and community housing in Montreal. Its scarcity increases crowding in interim housing and emergency shelters. In addition to the lack of available spaces, these groups have identified obstacles to accessing these limited spaces and sources of exclusion:

- a lack of knowledge about existing and available housing options for women;

- lengthy and intensive allocation procedures;

- eligibility criteria and organizations' rules and regulations;

- a lack of resources for those with complicated living situations.

There is no magic bullet: support is needed to develop a diverse range of housing resources and permanent, accessible and inclusive housing units that offer different levels of support to respond to Montreal women's varied needs.

Women's groups are organizing to develop these projects. It is just as necessary to fund community support as it is to support housing construction and associated community spaces. Groups have had enough of trading off on housing design, environment and available on-site services.

What social and community housing is available in Montreal?

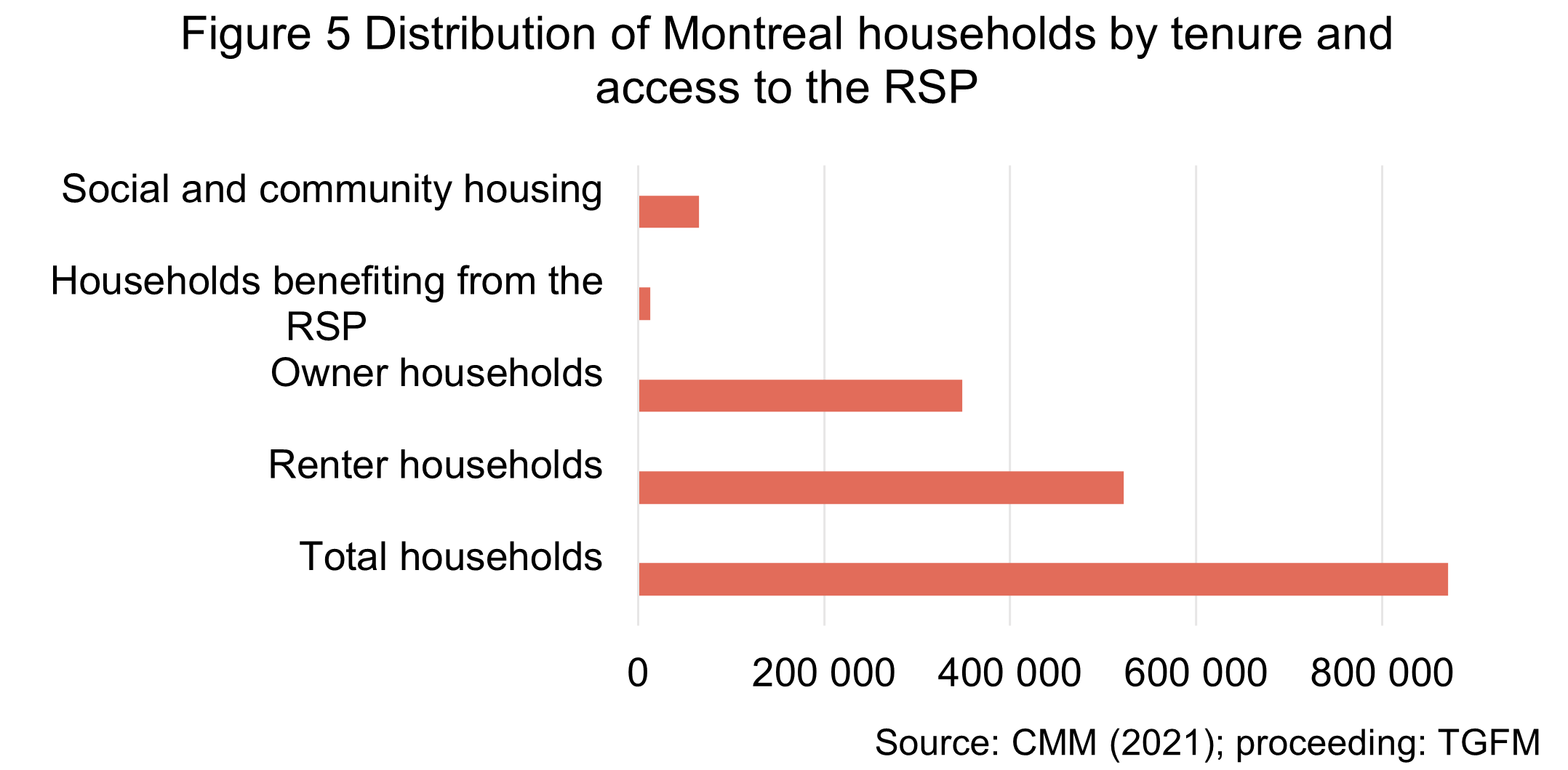

As shown in figure 5, 60% of Montreal households are renters. There are 65,695 community and social housing units on the island of Montreal, representing 13% of the rental market and 8% of the total housing stock. These low-income housing (Habitations à loyer modique, HLM), cooperative, and NPO housing units are a safety net for people who can no longer house themselves through the private market. In theory, they make excellent options for people trying to permanently leave a violent situation, regain housing stability or access housing adapted for someone living with a disability (Conseil des Montréalaises 2019), as well as for senior renters experiencing pressure from their landlords (Simard 2020).

Some of these units receive financial aid by way of the rent supplement program (RSP). In Montreal, 13,166 households (2.5% of renter households) benefit from the RSP, which allows them to limit their rent payments to 25% of their income. Renters in private housing can also benefit from the RSP.

Waiting to access it

More than 23,000 Montreal households are waiting for an HLM unit (OMHM 2021). The average wait time is five years, but wait times are longer for accessible and adaptable units and larger families (OMHM 2020). Due to a lack of maintenance, several hundred HLM units are currently sealed off and unoccupied. Thanks partly to funds obtained by the federal government's National Housing Strategy, the Office municipal d'habitation will receive an additional $100 million to renovate these HLM units (SHQ 2021a).

Most organizations that offer social housing have noted an increase in applications since the pandemic. Some organizations have even suspended their waiting lists to avoid giving people false hope.

"Applications have tripled since March 2020." (Mon toit, mon Cartier)

"Right now, we have 62 women on our waiting list and very few available units. We had to suspend our waiting list in order to manage expectations temporarily." (Réseau habitation femmes)

This situation is especially concerning for 2nd-stage housing organizations. These resources offer temporary housing for up to two years to continue the work started in shelters. In addition to protecting women and their children from violent ex-partners, these organizations help women rebuild and regain stability in their lives, allowing them to break the cycle of violence and prevent homelessness (Tanguy, Cousineau, et Fedida 2017). Yet, these organizations struggle to fulfil their missions: approximately 75% of requests are denied due to a lack of space. Of 54 spaces in Montreal, none is accessible to people with limited mobility (Marin 2021). Some organizations are working to address this significant shortcoming with new developments.

The housing crisis has complicated the process of leaving emergency shelters. Women who are victims of violence have priority access to HLM units. This priority can still take several months, as very few of these units open up, and some women have multiple children or require adapted housing. Other women fleeing violent situations are not recognized as priorities for HLM units, as they stay with loved ones rather than in women's shelters.

Issues in Access and Inclusion

Beyond the lack of space, several other issues lead to exclusion. To qualify for the regular RSP, for example, applicants must have been residents of the Montreal metropolitan area (CMM) for at least 12 months of the previous two years, be up to date on their tax declarations, and be a citizen or permanent resident.

"There is a desperate need for subsidized and safe housing that meets the many needs of women experiencing or at risk for homelessness. Overly restrictive criteria from the OMHM such as banning users from subsidized housing for three years following non-payment of rent, penalizing women experiencing precarity or struggling with multiple social problems." (Les Maisons de l’Ancre)

In addition to delays caused by waiting lists, the required documents and dense bureaucracy involved in allocating social housing create further barriers. Moreover, each NPO and housing cooperative s their mission and selection procedures, multiplying the steps to find housing. Access is especially limited for allophones, illiterate applicants, or those with bad experiences with institutional programs. Without application support for social housing offered by, among others, women's groups, finding and accessing social housing is nearly impossible (Garnier, Bernard, et Lacharité 2020). These groups support women in locating housing, obtaining the required documents (taxes, proof of residence, attestations, etc.), preparing for interviews and moving.

"The steps to access a program are usually seen as huge challenges (e.g., asking homeless women to provide proofs of address for the previous 12 months or tax returns), not to mention difficulties related to literacy and understanding when all of the programs require multiple-page forms with varying levels of language." (Réseau habitation femmes)

Many highlighted difficulties finding adequate resources that take the complexity of women's lived experiences into account. Organizations tend to focus on one problem only, even applying age limits, as in the case of mothers under 25. In addition to that, they aren't always equipped to appropriately accompany women experiencing complex situations stemming from recent or previous sexual violence, post-separation violence, immigration, legal antecedents, youth protection, mental health, drug use, post-traumatic stress, etc. Some organizations aren't adapted to these populations or have rules that exclude them. For example, some don't allow dogs, couples, sex work or drug consumption. The lack of social and community housing results in women not being able to choose their living environments. They are forced to accept the first housing that becomes available, even if the neighbourhood, living environment, rules or type of support provided do not correspond to their needs.

"One challenge for us is finding resources that are adapted to the lived experiences of the women in our community. Housing that is affordable, safe, but also open to guests and couples, allowing women to maintain their social and support networks." (Projets Autochtones du Québec)

"It's hard to find an appropriate reference for the women we work with. Often they don't fit into the services because of their complex situations (post-traumatic stress, precarity, drug or alcohol use, victims of violence, etc.)." (Concertation des luttes contre l’exploitation sexuelle)

"The majority of women we offer services to are situated at the intersection of multiple major challenges. Very few resources are designed to take all of those into account. To give just one example, resources for drug or alcohol use don't necessarily address physical problems that result from that, or vice-versa." (La rue des femmes)

"References are harder, lots of issues about children and youth protection services (which also has requests that often don't coincide with women's needs). Safety issues, too, (e.g., a woman experiencing intimate partner violence who is also suicidal... what's the best resource for that?)." (Multi-Femmes)

Social and community housing developed via the AccèsLogis program requires that 50% of building entrances be free of obstacles and 10% of units be adaptable. New social housing units should improve the accessible and adaptable stock due to the established norms. But still today, the construction and housing sectors lack knowledge, interest and sensitivity towards questions of accessibility, which has impacts on new housing and the inclusion of people living with disabilities, who tend to be selected towards the end of development. Involving them earlier in the project would allow for more efficient adaptation of units (Conseil des Montréalaises 2019).

Need for New Projects

The groups that responded to our questionnaire identified projects to develop to trim down waiting lists and refusals within their organizations. Given the variety in Montreal women with inadequate housing, more than one project type need to be developed. Emergency shelter spaces are needed with high thresholds for inclusion (sex work, drug use, with animals, trans individuals), transitional housing (both short and long term), second-stage housing, permanent social housing with various levels of support and housing cooperatives. The surveyed groups also insisted on projects targeting specific sectors or populations who have greater difficulty finding housing. To give some examples, families with children facing challenges, Indigenous women, newly arrived immigrants, asylum seekers and those without status, senior women who are sexual minorities, women leaving the sex industry, and families leaving a context of violence.

A survey of Indigenous individuals who visited Montreal organizations revealed that Inuit and First Nations women who currently live in Montreal don't necessarily wish to return to their communities of origin (Latimer, Bordeleau, et Méthot 2018). Their housing preferences are diverse, including subsidized autonomous housing, permanent housing in a building for Indigenous inhabitants that offers culturally adapted services, subsidized housing, temporary housing, Indigenous shelters or lodging houses. They want to be able to choose their living environments.

Senior women who are sexual minorities want access to housing within living environments to grow old together safely and in good health. They are often forgotten and rendered invisible. Despite that, they are mobilizing and have designed projects like the future Maison des RebElles. Upon completion, their housing project will lend itself to, among others, an environment that fosters support and mutual aid, with community spaces for gathering and the ability to freely welcome members of their chosen family who come to visit or support them during convalescence (Projet LoReLi 2021).

"As we can see throughout history, one of the main strengths of lesbian communities is to be able to mobilize and generate concrete actions in order not to be forgotten. We know that no one is thinking about us! Therefore, we must organize ourselves and create resources that meet our expectations, but especially our needs. (Quebec Lesbian Network)

Throughout these projects, applying the principles of universal accessibility in entryways and common spaces is crucial. Likewise, it's essential to plan for adaptable units and select tenants living with disabilities early on in the process to ensure that their homes are adapted according to their needs and realities (Conseil des Montréalaises 2019). This integration helps reduce construction costs and wait times and ensures the inclusion of women living with a disability in the project. Projects such as these also give women the choice of living where they want, rather than being restricted to living in one of a few available units.

What Challenges Are Associated with Living in Social and Community Housing?

Women make up a majority of all social housing residents, except in non-profit, mixed-gender housing for single individuals at risk for homelessness. The Fédération des OSBL d’habitation de Montréal (FOHM) demonstrated with its research action that women do not always feel safe in these environments: many of them experience bullying and harassment in common areas (Garnier, Bernard, et Lacharité 2020).

Women make up a majority of all social housing residents, except in non-profit, mixed-gender housing for single individuals at risk for homelessness. The Fédération des OSBL d’habitation de Montréal (FOHM) demonstrated with its research action that women do not always feel safe in these environments: many of them experience bullying and harassment in common areas (Garnier, Bernard, et Lacharité 2020).

For its part, the Fédération de l’habitation coopérative du Québec — Fédération des coopératives d’habitation intermunicipale du Montréal métropolitain (FHCQ — FECHIMM) has thoroughly documented the issues that limit women's participation in housing cooperatives. These include issues of work-family balance, sexual stereotypes and prejudice, as well as violence, bullying and harassment(FECHIMM 2018).

Community support in social housing is an essential pillar for residential stability for women with recent experiences of homelessness, as well as for those who are taking the next steps in their lives (e.g., ending a violent relationship, going back to school, finding a job, family reunification, leaving incarceration)(Whitzman et Desroches 2020; Garnier, Bernard, et Lacharité 2020; Savard 2018). This support is also crucial for defusing conflicts, screening for violence and fostering tenant engagement.

In our questionnaire, 70% of groups that offer shelter or housing for women in Montreal have suspended activities associated with community support or community life through the pandemic. An equal proportion established new practices to reach and support women. These activities take place remotely, by video call or telephone. Careful attention is paid to women experiencing isolation, don't have access to the internet, or have limited mobility through telephones, mail, home visits, food pantry deliveries, and solidarity walks. Some groups have created day camps for residents' children, libraries with activity kits and internet access points in their locations.

"We have adapted some of our services to continue responding to women's needs. Some activities were adapted around the reality of the pandemic, like art therapy over Zoom or therapy sessions over the phone. We did maintain some individual activities in-person while practicing social distancing." (La rue des femmes)

"We adapted our services for a virtual context to be able to continue following up with women. We adapted our workshops and activities for social distancing rules to allow the women in shelters to have activities. Only three at a time could participate. For women living outside of the shelter, we offered group workshops and coffee meet-ups on Zoom. It helped break some women's isolation." (Maison Dalauze)

Thanks partly to emergency funding, some organizations offered even more support to help counter the effects of isolation. Yet, organizations don't have stable and recurring funding to ensure this essential support (Savard 2018). This underfunding has adverse effects on tenants. Some programs had to reduce their support activities due to a lack of funding. This instability in funding, which predates the pandemic, prevents some organizations from developing new projects or pushes them to reduce the level of support offered, thereby asking tenants to take on more autonomy (Whitzman et Desroches 2020). In those cases, organizations are forced to turn away women who need more support.

How Do Women's Groups Work to Improve Social and Community Housing Stock?

Women's groups have been working towards the development of new social housing for decades. However, our consultation revealed that these resources are not widely known. Only half of the mixed-gender groups who responded to our questionnaire indicated that they had a good understanding of shelter and social housing resources for women (53%). Some efforts have been made to provide better references. Many organizations are involved in the community by participating in committees, offering training programs, and leading actions with various partners that raise awareness of their needs and the housing they offer. The Réseau d’aide aux personnes seules et itinérantes de Montréal (RAPSIM) published a directory of shelter and housing resources to help facilitate references between organizations (RAPSIM 2017).

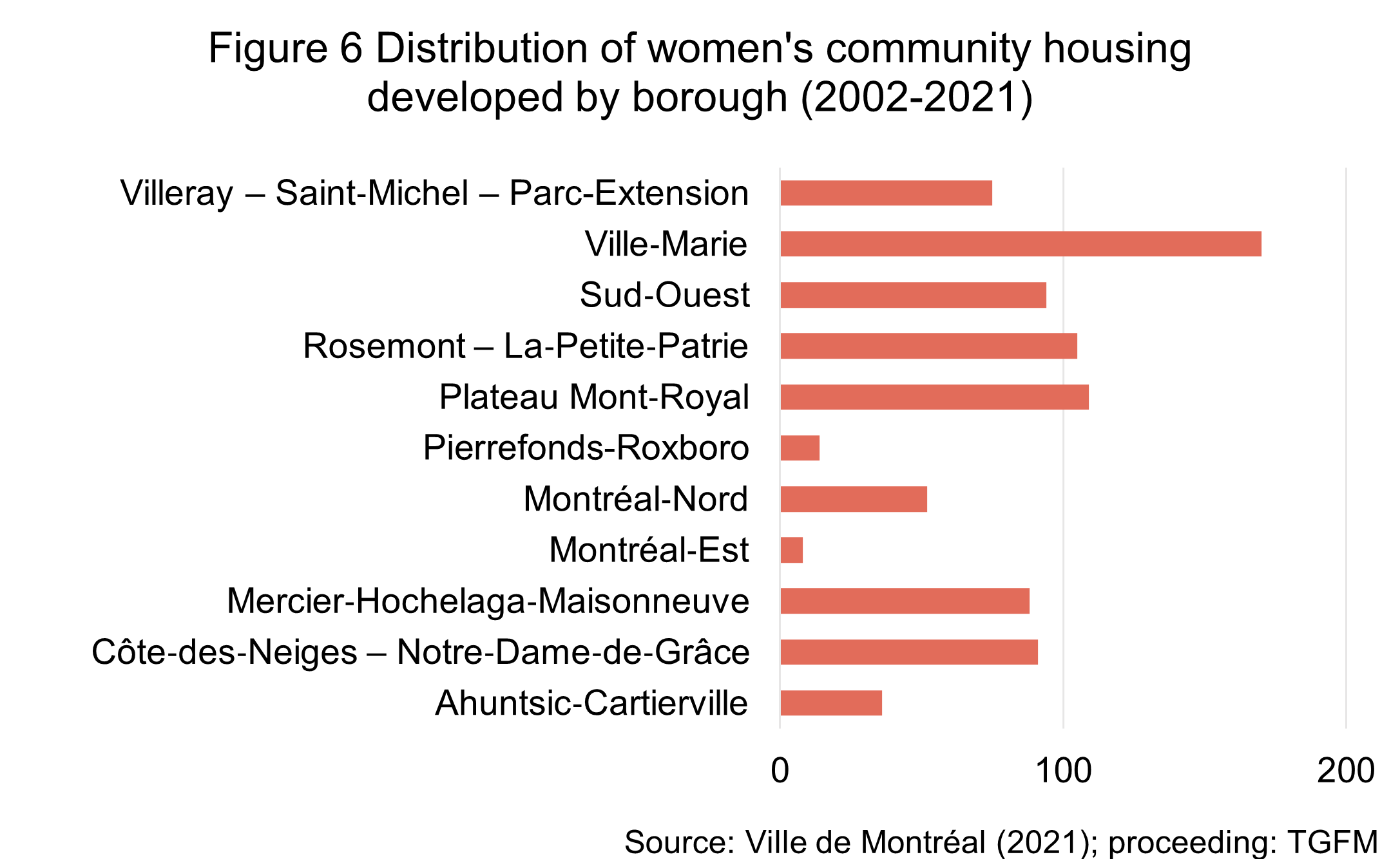

Since 2002, 32 organizations got involved in developing 42 community housing projects for women. This housing is for single women living alone or heads of single-parent households at risk for homelessness, leaving a violent situation or starting school. Some are reserved according to age, for young women or older women. These projects represent 842 homes that are constructed, inhabited or under construction. Each building has between 5 and 49 units (an average of 20) (Ville de Montréal 2021a).

As shown in figure 6, the majority of this housing is located in central neighbourhoods: Ville-Marie (170 homes in 9 projects), Rosemont—La Petite Patrie (105 homes in 6 projects), Sud-Ouest (94 homes in 6 projects) and Plateau Mont-Royal (109 homes in 3 projects). These figures betray the fact that no new community housing for women has been developed in multiple boroughs, namely Anjou, Lachine, LaSalle, L’Île-Bizard—Sainte-Geneviève, Outremont, Rivière-des-Prairies—Pointe-aux-Trembles, Saint-Laurent, Saint-Léonard and Verdun.

These projects were funded by the third wing of the AccèsLogis program, which supports the creation of temporary or permanent housing with support for populations with specific needs. More recently, three organizations developed projects thanks to the federal Rapid Housing Initiative (RHI) program and one more thanks to the third line of development of the City of Montreal's strategy for 12,000 housing units. These units for women make up a little over one of every four projects supported by these three programs, or 842 units out of a total of 3,350 (26%) (Ville de Montréal 2021a).

In our questionnaire, one-third of groups that offer shelter or housing for women in Montreal has had to slow development on a social housing project due to the pandemic. However, the pandemic increased interest in improving social housing stock, mainly due to increases in intimate partner violence and the role of housing in preventing illness.

"Our interest in development hasn't changed, no, especially because now we see the inequality even more and want things to finally change. Our ability, yes, because we can no longer gather." (Multi-femmes)

Many highlighted the importance of developing housing projects that provide privacy, good sound insulation, space for organizations' staff members, community spaces, storage, and green spaces (Garnier, Bernard, et Lacharité 2020). Attention was also paid to location so that women could be close to the services they need daily (e.g., grocery stores, pharmacies, daycare centres, public transportation, job hubs.) (Whitzman et Desroches 2020). However, land located near services is often very expensive or contaminated.

As social housing development over the past several years has been carried out through various programs, many disparities exist—for example, in terms of levels of financing for community support, exemptions from property tax, and eligible expenses during construction (Savard 2018). Due to the underfunding of the AccèsLogis program, many groups are forced to make concessions on the number of large units, size of the community hall, staff offices and the quality of materials (Savard 2018). Ces compressions entraînent des répercussions sur la qualité de vie sur place, mais également sur les relations entre locataires (Whitzman et Desroches 2020). These cuts have repercussions on the quality of life on-site, as well as relationships between tenants. Many groups reach for private financing sources to develop community halls that allow for culturally adapted services, support and community-building.

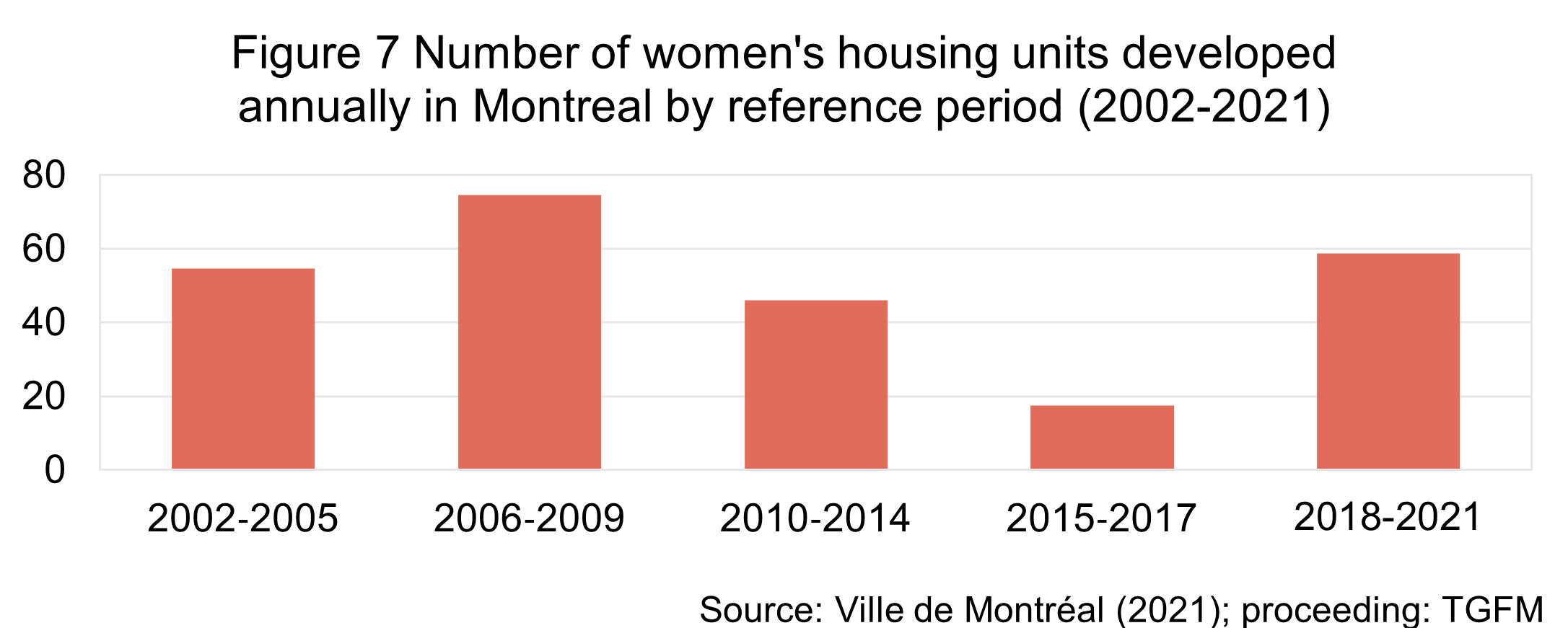

As shown in figure 7, the number of new community housing for women saw a dramatic decline between 2015 and 2017. Since 2018, we've seen a return to a rhythm of development comparable to the early 2000s, with roughly 58 homes per year. This return to normalcy is related to new investments and strategies adopted in recent years.

What Strategies and Policies Are Currently in Effect to Improve Social and Community Housing Stock?

Since 2020, the City of Montreal has implemented its own AccèsLogis program, which should resolve several problems the community housing sector identified (e.g., a minimum number of units for people with limited mobility, increases dung of eligible expenses.) However, this program remains dependant on provincial funding. However, no new funding was allocated in the last two provincial budgets. As a result, many women's groups have housing plans in mind but cannot make them a reality. The time between initial community mobilization and project launches grows increasingly longer. It's not uncommon for a decade to pass between a project idea and tenants arriving. This leads organizations to lose momentum and can slow their motivation to get involved in a new development.

In response to the housing crisis, municipalities took various measures to improve social and affordable housing stock. After public consultation, the City of Montreal adopted the Bylaw for a Mixed Montreal in 2020. This bylaw uses new residential projects to improve social, affordable and family housing stock. The bylaw finally went into effect in the spring of 2021. It remains to be seen if women's groups will benefit from this new lever.

In 2018, the City of Montreal committed to creating 12,000 social and affordable homes by the end of 2021 according to 5 lines of development (Ville de Montréal 2021b):

- Line 1. Developing social and community housing through existing programs

- Line 2. Practices to include affordable housing in new residential buildings

- Line 3. Innovative formulas for affordable housing that targets populations who are ineligible for existing programs

- Line 4. Protections for existing affordable social and private housing through renovation subsidies conditional on maintaining affordability

- Line 5. Supporting the acquisition of affordable properties (Access Condo program)

In June 2021, 10,886 units were created, or 91% of the target number. The delay is primarily for the 6,000 social and community units, notably due to minimal investments from the provincial government (Pelletier 2021).

That being said, it's essential to apply some nuance to these numbers. Of the 3,761 social and community housing units that have been counted towards the total, 2,818 are projects in development or under construction. It's also important to remember that "affordable housing", as defined by this strategy, is not necessarily affordable for the entirety of the population. The City definition of affordable housing is based on the median price or rent on the market: anything below that is considered affordable, regardless of what households can pay. Lastly, reaching this target does not mean that all units are new, as renovated or protected social or affordable housing units count towards the total under this strategy (line 4, 728 units).

Montreal is one of the cities that received funding as part of the federal government's Rapid Housing Initiative. $56.8 million was allocated to 12 affordable housing projects, which will offer more than 250 homes by early 2022. In the summer of 2021, a second RHI agreement was reached, and at least $56.3 million will go towards the rapid creation of social and community housing in Montreal (MAMH 2021). However, these federal investments are not systematically associated with rent supplement programs or subsidies for community support, as these are under provincial control. Organizations have to negotiate these subsidies with the Société d’habitation du Québec.

In October 2020, an agreement was finally reached that Quebec would obtain federal funds associated with the National Housing Strategy to increase and sustain available social housing. This strategy included provisions to allocate 25% of the investment to the needs of women, girls and their families, but Quebec was exempted from that target. The province asked to allocate the funds based on its priorities related to the AccèsLogis program, which does not have a target population.

As highlighted in the Quebec Auditor General's report, the Société d'habitation du Québec has not developed an intervention strategy or carried out analyses to ensure that its programs are used judiciously, including the AccèsLogis Québec program, to provide a maximum amount of help to households with housing needs (paraphrased from the original French quote Vérificateur général du Québec 2020, 3). This analysis must consider a wide range of information, including household needs, occupancy rates of affordable units, demographic trends, and the construction industry's capacity. From our perspective, this strategy must draw from a differential gender-based and intersectional analysis.

References

CMM. 2021. « Grand Montréal en statistiques ». Communauté métropolitaine de Montréal. 2021. http://observatoire.cmm.qc.ca/index.php?id=1048&no_cache=1&no_cache=1.

Conseil des Montréalaises. 2019. « Se loger à Montréal: Avis sur la discrimination des femmes en situation de handicap et le logement ». https://bit.ly/3xounFw.

FECHIMM. 2018. « Les coopératives d’habitation: présence des femmes, pouvoir des femmes. Rapport d’évaluation des besoins. » Fédération des coopératives d’habitation intermunicipale du Montréal métropolitain. https://cdn.fechimm.coop/uploads/documents/document/335/rapport-evaluation-projet-femmes-avril2018.pdf.

Garnier, Claire, Audrey Bernard, et Berthe Lacharité. 2020. « La sécurité des femmes dans les OSBL d’habitation pour personnes seules à Montréal ». Fédération des OSBL d’habitation de Montréal et Relais-femmes. http://fohm.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/FOHM_Rapport-final-20201124.pdf.

Latimer, Eric, François Bordeleau, et Christian Méthot. 2018. Besoins exprimés et préférences en matière de logement des utilisateurs autochtones de ressources communautaires sur l’île de Montréal. Montréal (Québec): Centre de recherche de l’Hôpital Douglas. http://reseaumtlnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Besoins-pre-fe-rences-logement-Autochtones-Version-16-fe-vrier-1.pdf.

MAMH. 2021. « Près de 1,5 milliard de dollars pour le logement abordable au Québec ». Ministère des Affaires municipales et de l’Habitation. 13 août 2021. https://bit.ly/3DYvKxh.

Marin, Stéphanie. 2021. « Femmes handicapées violentées: pas de maisons d’hébergement de 2e étape à Montréal ». L’actualité. 16 février 2021. https://lactualite.com/actualites/femmes-handicapees-violentees-pas-de-maisons-dhebergement-de-2e-etape-a-montreal/.

OMHM. 2020. « Rapport annuel 2019 ». Office municipal d’habitation de Montréal. https://www.omhm.qc.ca/fr/publications/rapport-annuel-2019.

———. 2021. « L’OMHM en chiffres | Office municipal d’habitation de Montréal ». 2021. https://www.omhm.qc.ca/fr/a-propos-de-nous/lomhm-en-chiffres.

Pelletier, Guillaume. 2021. « Stratégie de création de 12 000 logements sociaux et abordables: plus des trois quarts de la cible atteints ». Journal de Montréal. 17 février 2021. https://www.journaldemontreal.com/2021/02/17/strategie-de-creation-de-12-000-logements-sociaux-et-abordables-plus-des-trois-quarts-de-la-cible-atteints.

Projet LoReLi. 2021. « Pour contrer la pauvreté et l’insécurité des femmes marginalisées et de leurs familles : un soutien adéquat au logement social et abordable ». Présenté à mémoire déposé au ministre des Finances du Québec dans le cadre des consultations prébudgétaires 2021-2022, janvier. https://bit.ly/3raTKJS.

RAPSIM. 2017. Répertoire des ressources en hébergement communautaire et en logement social avec soutien communautaire. 7e édition. Réseau d’aide aux personnes seules et itinérantes de Montréal. http://rapsim.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Re%CC%81pertoire-WEB-VF.pdf.

Savard, Andrée. 2018. « Les projets d’habitation pour femmes monoparentales : Des initiatives structurantes à consolider et à développer pour contribuer à l’autonomie des femmes ». Comité consultatif Femmes en développement de la main-d’œuvre. https://ccfemme.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/ccf-avis_meres-monoparentales-et-projets-dhabitation_mars-2018.pdf.

SHQ. 2021. « Le gouvernement du Québec et le gouvernement du Canada ajoutent 100 M$ pour rénover plus de 500 logements d’habitations à loyer modique à Montréal ». Société d’habitation du Québec. 5 mai 2021. https://bit.ly/3l3Sapm.

Simard, Julien. 2020. « Vieillir et se loger en contexte de gentrification : la précarité résidentielle de locataires vieillissantes à Montréal ». Revue du CREMIS, novembre. https://www.cremis.ca/publications/articles-et-medias/vieillir-et-se-loger-en-contexte-de-gentrification-la-precarite-residentielle-de-locataires-vieillissantes-a-montreal/.

Tanguy, Adélaïde, Marie-Marthe Cousineau, et Gaëlle Fedida. 2017. Impact des services en maison d’hébergement: rapport de recherche. Trajetvi et L’Alliance des maisons d’hébergement de 2e étape pour femmes et Enfants victimes de violence conjugale. https://www.alliance2e.org/files/rechercheimpactfinal.pdf.

Vérificateur général du Québec. 2020. « Programme AccèsLogis Québec: réalisation des projets d’habitation ». Dans Rapport du Vérificateur général du Québec à l’Assemblée nationale pour l’année 2020-2021. https://www.vgq.qc.ca/Fichiers/Publications/rapport-annuel/165/vgq_ch04_shq_web.pdf.

Ville de Montréal. 2021a. « Projets de logements sociaux ou communautaires pour personnes ou ménages vulnérables 2002‐2021 : compilation – projets pour femmes ». Service de l’habitation.

———. 2021b. « Stratégie de développement de 12 000 logements sociaux et abordables ». Plans et stratégies. 2021. https://montreal.ca/articles/strategie-de-developpement-de-12-000-logements-sociaux-et-abordables-13890.

Whitzman, Carolyn, et Marie-Eve Desroches. 2020. « Le logement pour les femmes trouver l’équilibre entre la croissance et le care à Montréal, Gatineau et Ottawa ». https://cmhc.ent.sirsidynix.net/client/en_US/CMHCLibrary/search/results?qu=whitzman&te=ILS.