Montreal Women’s Right to Housing: We’re Working on It, Are You?

Finding Adequate Housing in the Middle of a Crisis

The housing crisis is not over. It continues to have an outsize effect on Montreal women, whose housing needs and challenges have only increased with the pandemic. The issues are related to:

The housing crisis is not over. It continues to have an outsize effect on Montreal women, whose housing needs and challenges have only increased with the pandemic. The issues are related to:

- rent increases and shortages in affordable housing;

- the many prejudices that feed into discrimination and competition in the rental market;

- undersized and unsafe housing that threatens women's health and safety;

- the lack of accessible and adapted housing, which limits the autonomy of women living with a disability;

- increases in evictions and landlord repossessions of units, as well as difficulties exercising their rights;

- harassment from landlords or neighbours, which threatens tenant’s security at home.

Is There a Housing Crisis in Montreal?

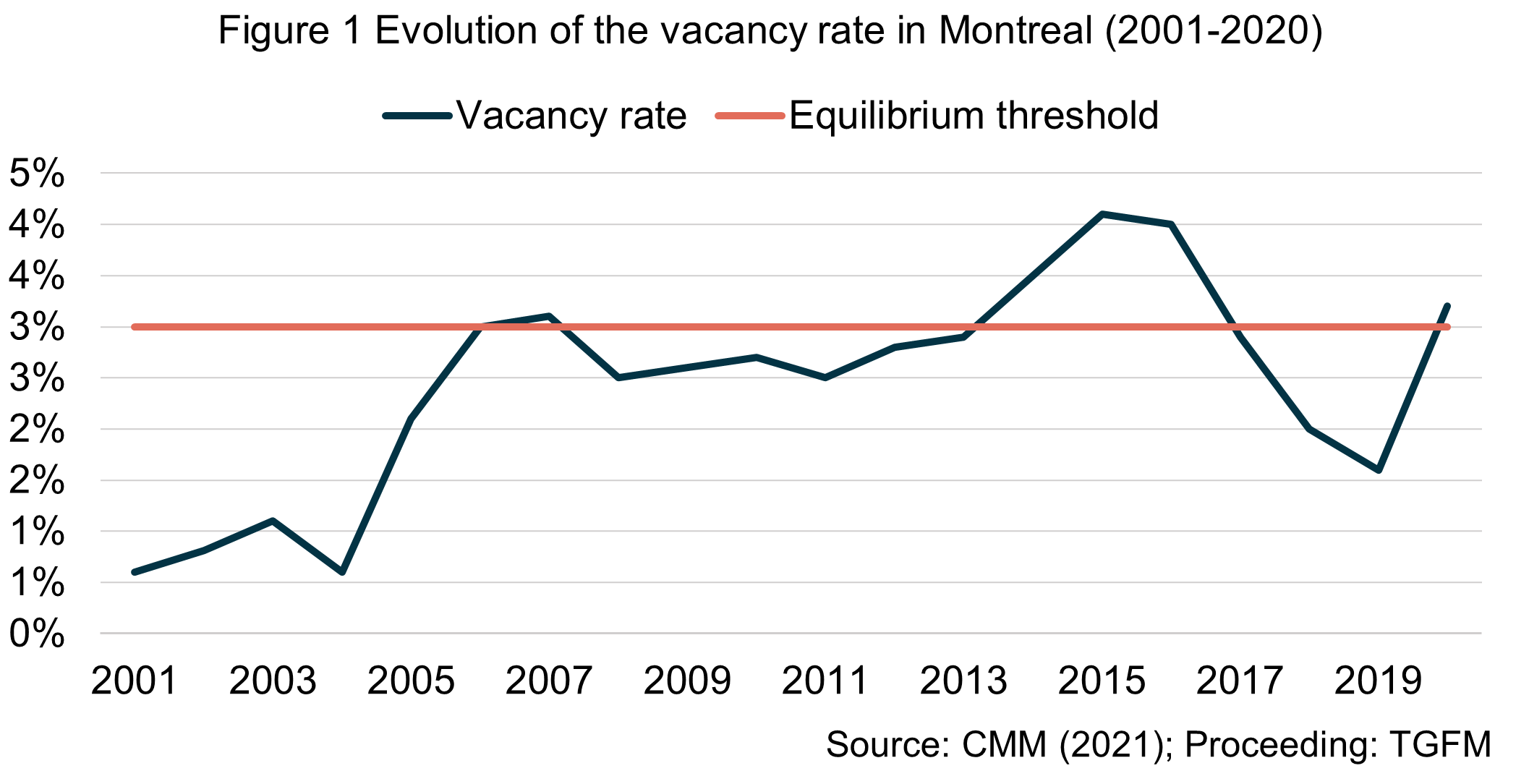

The COVID-19 pandemic has transformed our lives, our routines and our relationship to housing. Since the pandemic, access to adequate housing has been crucial during lockdowns and for preventing illness, but also for school and telework. At present, this access is not equitably distributed, primarily due to the housing crisis. A situation is deemed a housing crisis when the rental unit vacancy rate drops below 3%, and this causes renters to experience more difficulty finding housing that meets their needs.

Vacancy in Rental Units

Some elected officials have claimed that there is no housing crisis, as 3.2 % of units in Montreal were vacant in 2020 (figure 1).

Many units did become available during the pandemic due to online learning, telework and the standstill in tourist rentals. For that reason, certain types of units showed higher vacancy rates (SCHL 2020) :

- Studios (5.1%) and one-bedroom units (3.4%)

- Units in the Ville-Marie borough (10.2 %)

- Units with rents over $1,000 (6.7%)

In contrast, vacancy rates stayed very low in other categories(SCHL 2020):

- Units located in the Montréal-Nord (0.6%), Ahuntsic-Cartierville (1.2%) and Pointe-aux-Trembles—Montréal-Est (1.9%) boroughs

- Units for families (more than 3 bedrooms) located in the Rosemont—La Petite-Patrie (0%), Montréal-Nord (0.1%), Mercier (0.2%), Villeray–Saint-Michel–Parc-Extension (0.2%) and Sainte-Geneviève—Senneville (1.2%) boroughs

New Construction: A Solution to Address the Shortage?

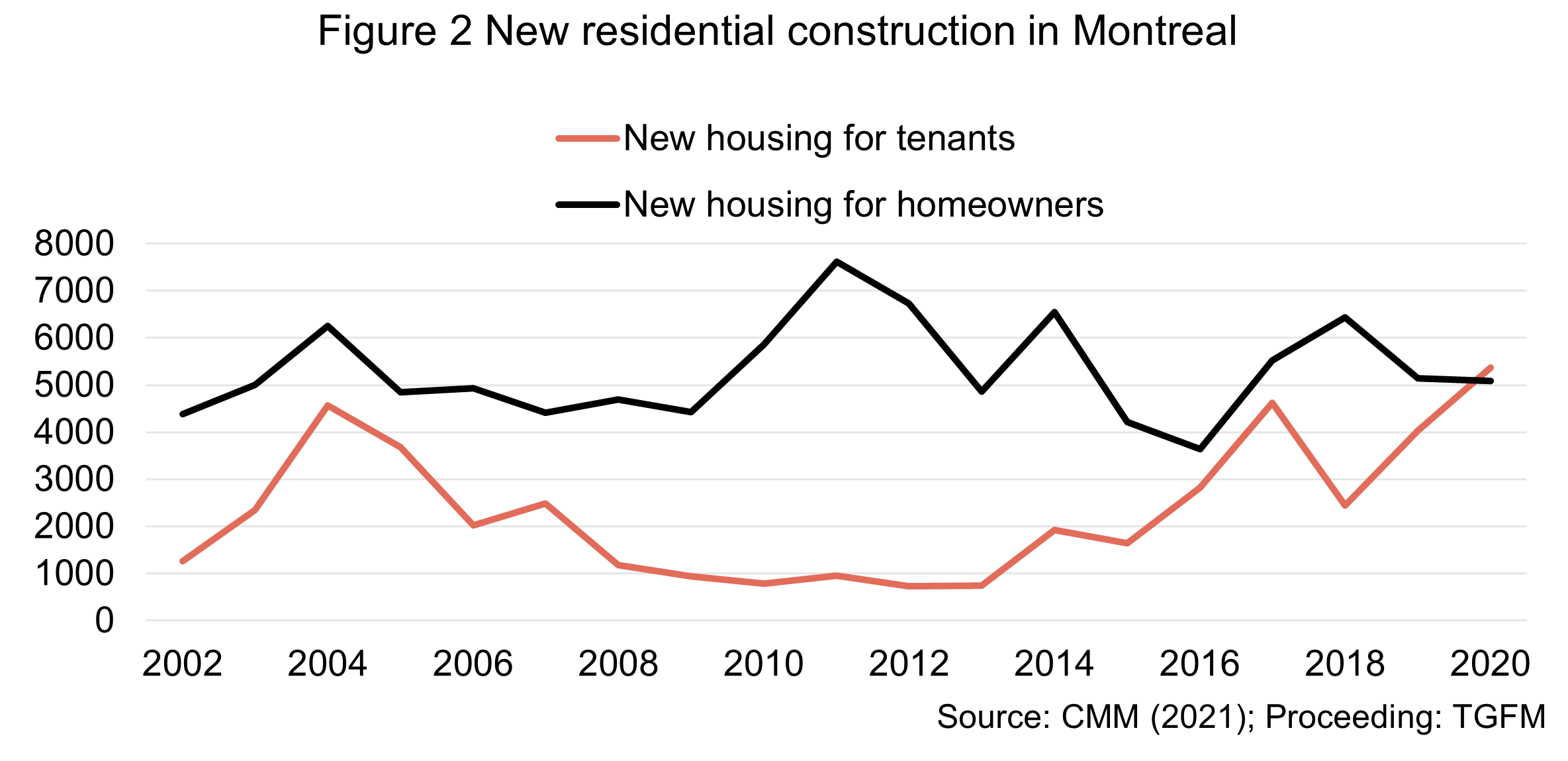

One interesting and even encouraging fact is that, in 2020, most new housing units (51%) were designated as rental properties (figure 2). In addition, an increasing share of condominiums are rental units. In 2020, renters inhabited 21% of condos (SCHL 2020).

However, several issues should be noted here. New construction is concentrated in specific sectors and is primarily carried out by the private sector. We see a slowdown of new construction led by cooperative and non-profit organizations(CMM 2019).

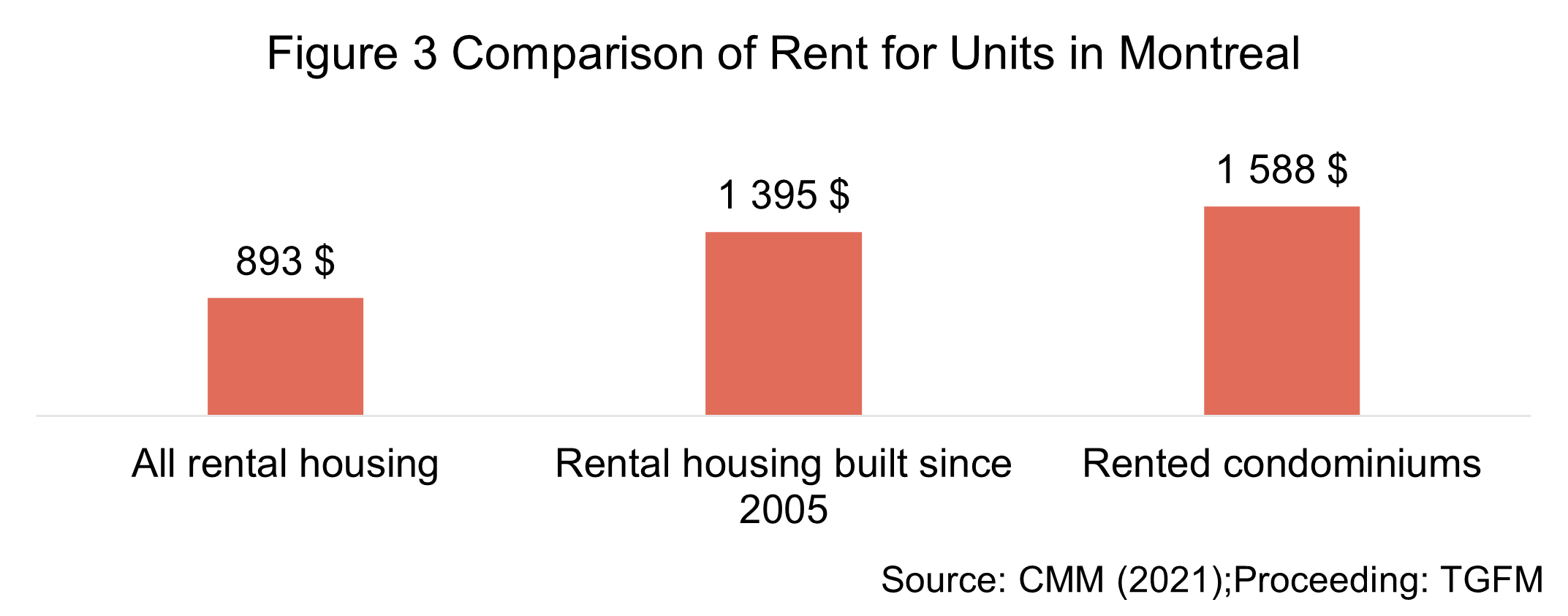

These new units do not address the shortage of affordable rental units. As shown in figure 3, the corresponding rents are significantly higher: while the average monthly rent for a unit in Montreal is $893, the average monthly rent is $1,395 for a unit built after 2005 and $1,588 for rented condominiums(SCHL 2020).

We are Indeed Experiencing an Affordable Rental Housing Crisis

This crisis is especially acute in specific sectors and for families. Available units do not fit the budgets of many renter households. As a result, 128 Montreal households were without housing on July 1, 2021, not including those who maintained residence or moved into inadequate housing out of fear of ending up on the street (FRAPRU 2021).

What is adequate housing, then? First of all, adequate housing is much more than four walls and a roof overhead. Here, governments generally agree on three other criteria:

- Affordability: less than 30% of income goes toward housing expenses (rent, heating, etc.)

- Quality: Major repairs needed (floor, walls, roof, plumbing, electricity, etc.)

- Size: Adequate number of bedrooms for the household size

A household is experiencing a core housing need if one of these criteria is not met and if the household income is insufficient to allow it to move to adequate housing in the same region. On the island of Montreal, 117,115 households (13% of all households) are experiencing core housing needs (CMM 2021). Specific populations are more regularly experiencing core housing needs (CMM 2021; SCHL 2021):

- 7% of renter households versus 3.9% of homeowner households

- 5% of families with a single female parent versus 5.2% of dual-parent families

- 5% of women over 65 living alone versus 23% of single-person households

- 5% of households with at least one person who has activity limitations versus 12.5% of other households

- 9% of recent immigrant households (2011-2016), 21.5% of people without permanent resident status and 17.4% of immigrant households versus 13.2% of non-immigrant households

- 21% of Indigenous households versus 14.9% of non-Indigenous households

Additionally, the concept of core housing needs leaves out several other aspects of adequate housing. The United Nations proposes seven essential criteria to ensure the right to housing (ONU Habitat 2005) :

- Security of tenure: no threats of eviction, harassment, expropriation, etc.

- Availability of services, materials, facilities and infrastructure: electricity, potable water, waste management, etc.

- Affordability: housing costs must not compromise other fundamental rights like food, education and health

- Habitability: adequate space, without problems related to physical safety, insulation or repair needs

- Accessibility: possibility to move about the space without obstacles and adapt the unit for limitations

- Location: proximity to businesses, services and employment opportunities

- Cultural adequacy: respects the expression of cultural identity and is free from violence

Women who interact with the surveyed groups expressed housing issues and needs that refer to every one of these criteria. Nearly every (95%) group that responded identified an increase in the number of aid requests since the start of the pandemic.

Infringements on Women's Right to Housing in Montreal

Women who interact with the surveyed groups expressed housing issues and needs that refer to every one of these criteria. Nearly every (95%) group that responded identified an increase in the number of aid requests since the start of the pandemic.

Affordability

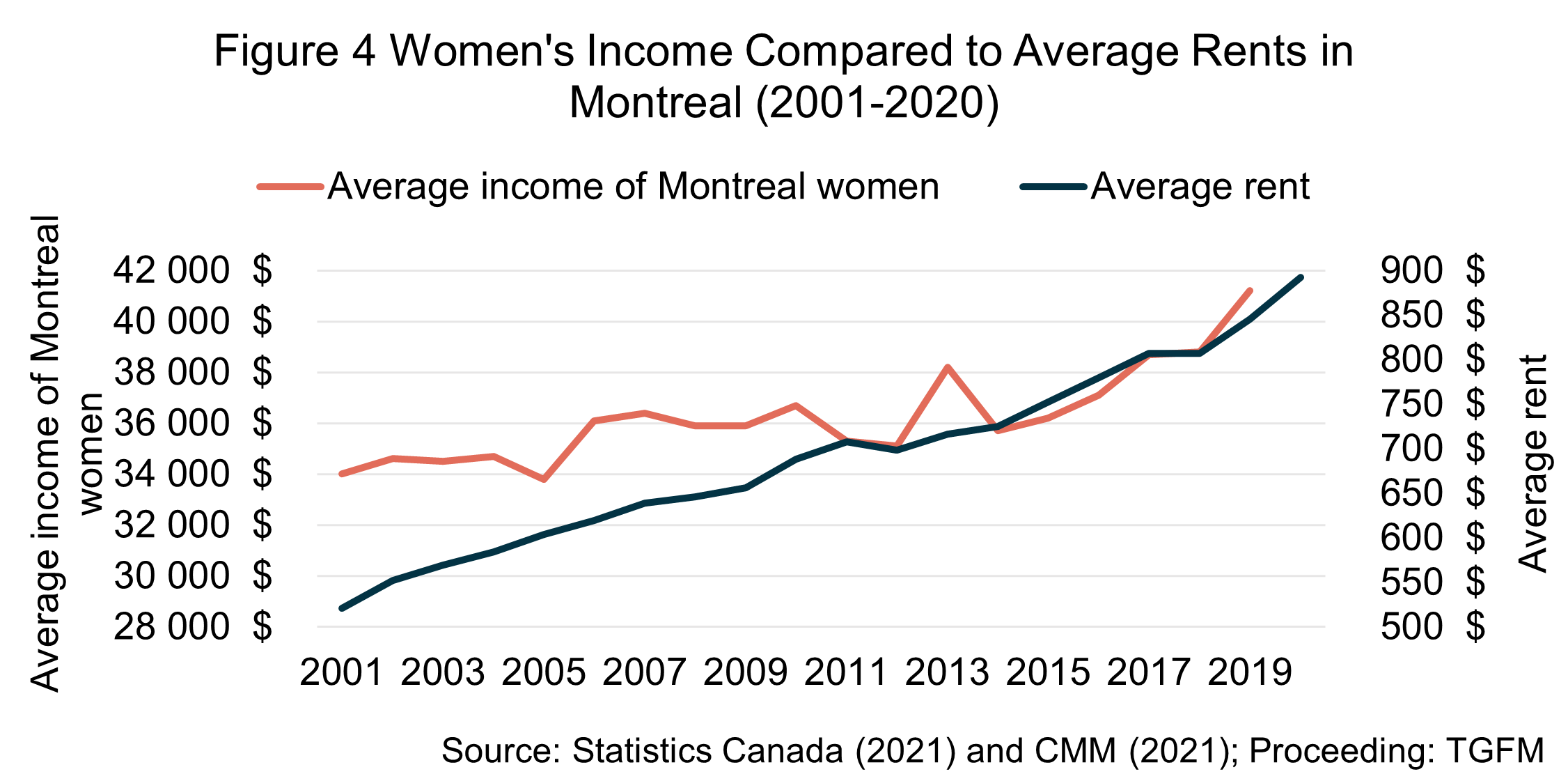

According to our questionnaire, 89% of groups estimate that women in Montreal have had more difficulty finding affordable housing since the pandemic. The persistence of the wage gap can explain this: women's median income is only 82% of men's median income (Statistique Canada 2021). This gap is likely only to widen with the pandemic, as women were affected more by job loss, especially those working part-time or in the service sector (restaurants, hotels and shops). Moreover, recovery was slower for lower-paid jobs traditionally worked by women and people of colour (Bastien, Morel, et Torres 2020).

We have observed an intersectional feminization of poverty. In other words, some women are placed in more precarious situations than others. These women experience discrimination on a more frequent basis and face more obstacles in their daily lives because, for example, they are the head of a single-parent household, are immigrants, identify as members of a sexual minority, are living with a disability or are racialized (Celis, TGFM, et COSSL 2020). Among other issues, these obstacles can affect access to education, jobs, and, consequently, an adequate income for housing.

In parallel, we also observed an increase in average monthly rents. In Montréal, this increase was 4.6% from 2019 to 2020 (SCHL 2020), well over inflation (2.3%) and the proposed index from the Tribunal administratif du logement (TAL) (1.2% for a unit where heating is not included in rent) (TAL 2020). These increases were more striking in boroughs undergoing gentrification. For example, in the Southwest and Verdun, average monthly rents increased from $808 to $924. As shown in figure 4, rents are increasing more quickly than the average income of women in Montreal.

For low-income women, it has become increasingly challenging to find affordable housing. Rent for vacant units is currently 36% higher than average ($1,202 versus $883). This disparity is especially striking in areas like the Southwest and Verdun, where rents for vacant units are 74% higher ($1,574 versus $905) (SCHL 2020). Many neighbourhoods in Montreal have good access to public transportation, local businesses and services, but most of these areas are gentrifying and becoming less affordable. In addition, the social, economic and cultural life of these neighbourhoods is changing, causing households to lose their reference points (Projet de Cartographie Anti-éviction de Parc-Extension 2020). 38% of surveyed groups mentioned that Montreal women experienced greater difficulty finding housing near services since the pandemic. They are often forced to move to more far-flung neighbourhoods with limited services, negatively affecting their health and wellbeing. This can lead to isolation, food insecurity and fatigue due to longer commuting times.

Many Montreal women are forced into unaffordable housing or accepting rent increases for fear of being unable to rent elsewhere. Housing is usually a household's most significant expense. Unaffordable housing has major impacts on financial stability, especially among women who are Indigenous, living with a disability, seniors, sexual minorities, immigrants or single parents, all of whom are more likely to have lower incomes. In addition, single parents women have only one income with which to cover their family's housing costs. Lesbians and other women who are in relationships with women are doubly affected by wage inequality(Fontaine, Antoine, et Vaillancourt 2021) since these couples are often composed of two women, and that their salaries are lower than those of men and those of heterosexual women. These women are more likely to take on debt and limit their other expenses, such as transportation, food, education, clothing, medications and leisure. Over the long term, this precarity creates insecurity―they are only one new expense or one drop in income away from defaulting on a payment.

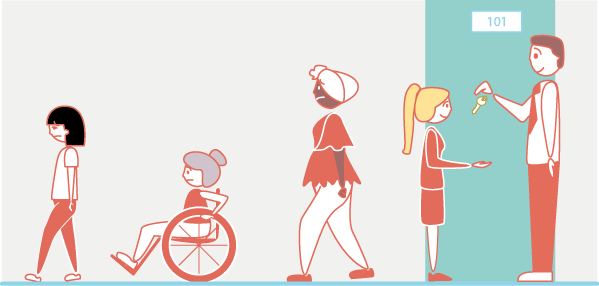

Discrimination and Competition for Rentals

Landlords are incredibly selective right now, opening the door for discrimination. According to our questionnaire, 55% of surveyed groups noted that women in Montreal are facing more rental discrimination since the pandemic. This situation poses a daunting challenge to those with low incomes or without good credit scores, proof of stable employment or good references.

According to these groups, these situations are especially common for women who are newly arrived immigrants, have recently left an institution (e.g., detention centre or youth centre), are the head of a single-parent family, have precarious status, are living with a disability, are sexual minorities, are fleeing an abusive relationship, or are sex workers.

"The criminalization of sex work makes our income illegal and often prevents us from having a credit history or proof of income. This makes us ineligible for subsidized housing. If we receive social assistance, we can access housing, but we'll live in constant fear of being sued to repay this assistance, plus taxes." (Stella, l’amie de Maimie)

"We work with women who experience the consequences and impacts of intimate partner or domestic violence. They often face multiple systems of oppression. Some women experience financial abuse and as a result, have very poor credit. The wait time for an HLM unit is very long and finding housing with poor credit can be very tricky. The same goes for women who end up with Régie du logement files because of a violent partner or who have a bad reference from a previous landlord." (Maison Dalauze)

"The women we work with have left prison. For them, it's one additional barrier to finding appropriate housing or taking housing insurance, because of the prejudices they face. Accessibility of affordable housing is an urgent issue for society. Everyone has the right to housing." (Société Elizabeth Fry du Québec)

This discrimination is fed by a range of prejudices on single parenthood, social assistance, disabilities, refugees, lesbophobia and intimate partner violence(Savard 2018; Conseil des Montréalaises 2019). In order to access adequate housing, some women are forced to lie about their situations :

"It is very difficult for women to find affordable, safe housing that is fit for occupation. They experience widespread discrimination based on their incomes, family composition because they are victims of abuse, because they are immigrants, because they are women of colour, etc. This leads them to choose what they would like to share about their lives with potential landlords. Being fully transparent is more likely to result in discrimination than empathy." (Le Parados)

"Homophobia is still very present in our society, as is sexism. Sexually diverse women experience a phobia that combines these two systems, namely lesbophobia. In order to minimize some of the impacts of these phobias and to have access to adequate housing, many will lie about their marital status to avoid discrimination or be victims of violence. This is a major setback for us, as some sexually diverse women have to hide to protect themselves. (Quebec Lesbian Network)

Undersized and unhealthy housing

According to our questionnaire, 42% of groups reported that women in Montreal had had more difficulty finding adequately sized housing since the pandemic. As we showed earlier, large units are already a rarity on the market, especially in specific neighbourhoods. Living in a too-small unit through a lockdown and curfew is especially demanding and could intensify conflicts and situations of harassment and violence both within households and with neighbours.

38% of surveyed groups noted that requests for intervention due to unsafe housing conditions for women in Montreal have increased with the pandemic. Lockdowns expose more households to mold and vermin, affecting their health (e.g., anxiety, hypervigilance, isolation, depression). Among other concerns, many women hesitate to raise these problems with their landlords out of fear of being evicted or subjected to a rent increase or because they have previously experienced sexual harassment (Frederic Hountondji 2021). Additionally, fewer than half of the women's groups surveyed (41%) stated that they were well aware of the avenues available to them in terms of housing rights. These groups often redirect women to their neighbourhood's tenant association.

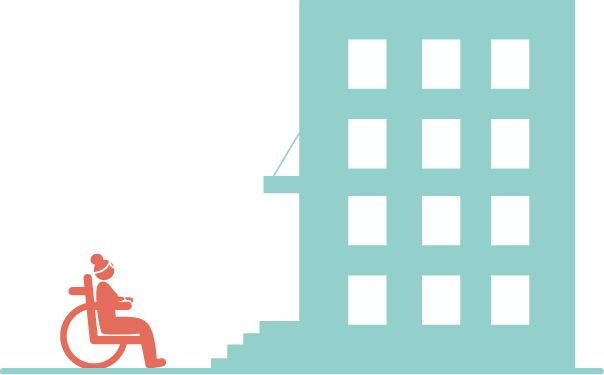

Inaccessible Housing for Women Living with Disabilities

One-quarter of surveyed groups stated that women in Montreal had experienced greater difficulty finding accessible or adaptable housing or retrofitting housing to be accessible since the pandemic. It should be noted that the housing crisis is essentially permanent for people living with a disability. We don't know how many accessible or adaptable units there are in Montreal. Most social and community housing units in Montreal are accessible or adaptable for a person living with mobility limitations (56.8 %) (Ville de Montréal 2016). However, these units are primarily limited to seniors or are very small, which can be a problem for renters who need more space to move freely or live with their families or caregivers (Conseil des Montréalaises 2019).

There are very few accessible and adaptable units on the private market. One of the reasons for this is that most units were built before 1980 (71%). Often, these units cannot be adapted. They also tend to receive less light, which poses challenges and obstacles daily for women who are blind, have low vision or are Deaf. The lack of soundproofing disproportionately affects blind women, autistic women and those with a child on the autism spectrum (Conseil des Montréalaises 2019).

The requirement that new housing units meet adaptability standards should help to address the lack of accessible units (RBQ 2021). Yet, these standards are not comprehensive; they are based solely on accessibility for motorized wheelchairs. Frequently, these new units are too expensive for women living with a disability, who are more likely to be part of a household that falls under the low-income threshold (OPHQ 2021). As a result, they are more likely to need subsidized housing to live in an adequate unit.

The lack of accessibility creates challenges that limit their ability to care for themselves, their children and their home daily. This can result in unsafe or cluttered living conditions, potentially eviction or a call to youth protection services (Conseil des Montréalaises 2019). The lack of accessible and adaptable housing means that some women are forced to live in long-term care centres (CHSLDs) or private senior living facilities (Conseil des Montréalaises 2019).

Evictions, Threats and Landlord Repossession

While the Tribunal administratif du logement (TAL, formerly the Régie du logement) put a hold on evictions during the first wave of the pandemic, this hold was lifted in July 2020. According to our questionnaire, 53% of surveyed groups reported that women in Montreal are increasingly faced with threats, evictions, harassment and landlord repossessions of their homes since the pandemic. This finding comes primarily from housing committees, which have seen an increase in requests for help with evictions and landlord repossessions (Projet de Cartographie Anti-éviction de Parc-Extension 2020), and from the Office municipal d’habitation de Montréal (OMHM 2020).

These issues are the result of several circumstances forcing many renter households to leave their homes. Montreal has undergone a wave of conversions from rental units into undivided co-ownership properties. From 2011 to 2019, up to 4,000 rental units were converted into co-ownership properties, mainly in central districts (SCHL 2021). Landlord repossessions and evictions due to major renovation work (renovictions) are increasingly common. These forced moves are especially difficult for women who are seniors, living with a disability or immigrants as they undermine their support networks (friends, family, home care, community organizations, local businesses, etc.) (Conseil des Montréalaises 2019; Projet de Cartographie Anti-éviction de Parc-Extension 2020).

The Comité Logement de La Petite-Patrie studied 363 notices of landlord repossession or eviction due to major renovations. They found that 85% of landlords who evicted their tenants used fraudulent and malicious strategies to bypass tenants' right to security of tenure (CLPP 2020). These maneuvers are sometimes accompanied by harassment:

"Many women are harassed by landlords trying to get them to sign a lease termination. Often they won't know their rights and will cede under pressure and sign. Sometimes this can take the form of sexual blackmail when it comes to making repairs to a unit or negotiating rent, for example." (POPIR comité logement)

While it's possible to contest these evictions, housing committees have found that very few files succeed (Projet de Cartographie Anti-éviction de Parc-Extension 2020). On top of that, the organizations surveyed noted that many women struggle to use the judicial system to uphold their rights. Among other challenges, this can be explained by limited knowledge of housing rights, the complexity of procedures, the expenses involved, language barriers, or simply the fatigue inherent in constantly defending their rights.

Harassment and Violence

For several years, the Centre d'éducation et d'action des femmes (CÉAF) has shed light on sexual assaults experienced by renters and lodgers. They are aware of the taboos and silence surrounding this violence, which can occur in social, community or private housing contexts (CEAF 2021). According to our questionnaire, 53% of groups stated that women in Montreal had had more difficulty finding respectful living environments since the pandemic.

Many women who are single parents, racialized, sex workers or living with a disability have experienced harassment from landlords or neighbours. The combination of housing crisis and pandemic has trapped some women in situations of harassment:

"With sex work considered a criminal act since 2014, sex workers can be evicted if our landlords find out that we work out of our homes. These evictions can be formally carried out with the Régie or informal, including threats, extortion and violence." (Stella, l’amie de Maimie)

"The violence seems to be increasing. Living environments are tenser. Some landlords have more free time and want to take advantage of it to carry out renovations, but women don't want that out of fear of contracting the virus. Housing sales have increased in some areas and, along with them, visits, harassment and illegal evictions." (Regroupement des comités logement et associations de locataires du Québec)

It is challenging for senior women who are sexual minorities to find respectful living environments. In addition to experiencing financial precarity, they are more likely to grow old in isolated and marginalized conditions. They have less support from their families, as many have no children and have broken ties with siblings who did not accept their sexual orientation. Mostly, residences, NPOs and other living environments for seniors are often heteronormative spaces where homophobia and lesbophobia are still widespread. These women are afraid to divulge their sexual orientation or have visits from partners or their chosen family out of fear of stigma, being underserved by the health and social services network or experiencing daily microagressions afterwards. They go back into the closet to protect themselves (Projet LoReLi 2021).

« Seniors from our communities have fought for legal equality and now they have to go back to the closet because they face discrimination or violence related to their sexual orientation or gender identity. It's really sad to see that de facto equality is far from being achieved for our communities, even though a lot has been done. » (Réseau des lesbiennes du Québec)

What is the Government's Response to the Housing Crisis?

Municipalities in Quebec have committed to supporting households in need of housing. Since 2005, the Office municipal d’habitation de Montréal (OMHM) has received a budget from the city to offer a reference and support service (Ville de Montréal 2021c). In 2021, close to 180 households experiencing difficulties were accompanied by this service. The City also offers temporary housing and help with storage and moving.

The provincial government established an emergency rent supplement program (RSP) in response to the housing crisis. The criteria to access this subsidy have been loosened, allowing low-income households to limit housing costs to only 25% of their income. For example, people without status in Canada who are victims of intimate partner violence are eligible, despite otherwise being excluded from the RSP (SHQ 2021b). RSPs are still challenging to use in practice, as very few available units qualify for the program, either because the rent is too high, the landlord refuses to participate, or a lack of understanding of how the program works within municipal housing offices. Following a $1.1 billion deal with the federal government, the Shelter Allowance Program (SAP) was reinforced. The SAP offers up to $80 per month in financial support for low-income households (MAMH 2021).

Some Montreal boroughs have adopted bylaws to protect their rental housing stock. Eight boroughs have adopted bylaws to regulate subdivisions and any reduction to the number of units, joint maneuvers in the case of renovictions. These bylaws have been contested by landlords, many of whom have applied considerable pressure to reduce their application in specific sectors (CORPIQ 2020).

Several boroughs have restrictions on short-term tourist rentals (e.g., Airbnb), whether confining them to specific areas or requiring permits. Other measures should still be considered to maintain affordable rental housing. Indeed, demand for housing will increase again when health measures are loosened due to increased tourism and a return to classrooms and offices.

The Residential Adaptation Assistance Program (RAAP) helps adapt homes for people living with disabilities. This program has had major shortcomings in the past (long waits, insufficient eligible costs, eligibility criteria, landlord refusals, etc.) (Conseil des Montréalaises 2019). Thanks to its new status as a metropolis, the City of Montreal developed its program, adapted to its specific needs. The Montreal Home Adaptation Program was launched in April 2020 and increased the maximum subsidy amount from $16,000 to $35,000, giving more control over the choice of adaptations to be made to the person living with a disability. The new program also expands access to all people living with disabilities, regardless of their immigration status (Ville de Montréal 2020).

References

Bastien, Thomas, Anne-Marie Morel, et Sandy Torres. 2020. « Impact de la pandémie de COVID-19 sur la santé et la qualité de vie des femmes au Québec ». Association pour la santé publique du Québec. https://www.aspq.org/app/uploads/2020/12/rapport_femmes-et-covid_impact_de_la_covid_sur_la_sante_et_qualite_de_vie_des-femmes_au_quebec.pdf.

CEAF. 2021. « Femmes et logement ». Centre d’éducation et d’action des femmes de Montréal. 2021. https://www.ceaf-montreal.qc.ca/public/femmes-et-logement.html.

Celis, Leila, TGFM, et COSSL. 2020. « Groupes communautaires et femmes en situation de pauvreté à Montréal: besoins, pratiques et enjeux intersectionnels ». https://www.tgfm.org/nos-publications/66.

CLPP. 2020. « Entre fraude et spéculation: enquête sur les reprises et évictions de logement ». Comité logement de la Petite Patrie. https://comitelogementpetitepatrie.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Entre-fraude-et-spe%CC%81culation-2020.pdf.

CMM. 2019. « Pénurie de logements locatifs et ralentissement de la construction de logements sociaux et abordables ». Perspective grand Montréal: un bulletin de l’observatoire grand Montréal, Communauté métropolitaine de Montréal, juin 2019. https://cmm.qc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/39_Perspective.pdf.

———. 2021. « Grand Montréal en statistiques ». Communauté métropolitaine de Montréal. 2021. http://observatoire.cmm.qc.ca/index.php?id=1048&no_cache=1&no_cache=1.

Conseil des Montréalaises. 2019. « Se loger à Montréal: Avis sur la discrimination des femmes en situation de handicap et le logement ». https://bit.ly/3xounFw.

CORPIQ. 2020. « Droit de propriété : victoire symbolique de la CORPIQ contre la Ville de Montréal ». Corporation des Propriétaires Immobiliers du Québec. 17 décembre 2020. https://bit.ly/3FNlB75.

Fontaine, Eugénie, Julie Antoine, et Julie Vaillancourt. 2021. « Enquête 2020: portrait des femmes de la diversité sexuelle au Québec ». Réseau des lesbiennes du Québec (RLQ). https://bit.ly/3l9PIh0.

FRAPRU. 2021. « Bilan du 1er juillet : le FRAPRU exige des mesures structurantes pour sortir de la crise ». Front d’action populaire en réaménagement urbain. 2 juillet 2021. https://www.frapru.qc.ca/bilan1juillet2021/.

Frederic Hountondji. 2021. « La Marie Debout dénonce l’insalubrité des logements dans MHM ». Journal le Métro. 19 février 2021. https://bit.ly/3DOFRol.

MAMH. 2021. « Près de 1,5 milliard de dollars pour le logement abordable au Québec ». Ministère des Affaires municipales et de l’Habitation. 13 août 2021. https://bit.ly/3DYvKxh.

OMHM. 2020. « Rapport annuel 2019 ». Office municipal d’habitation de Montréal. https://www.omhm.qc.ca/fr/publications/rapport-annuel-2019.

ONU Habitat. 2005. « Le droit à un logement convenable ». Fiche d’information no 21. Nations Unies, Haut commissariat aux droits de l’Homme. https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FS21_rev_1_Housing_fr.pdf.

OPHQ. 2021. « Les femmes avec incapacité au Québec, un portrait statistique de leurs conditions de vie et de leur participation sociale ». Office des personnes handicapées du Québec. https://bit.ly/3nQLpJm.

Projet de Cartographie Anti-éviction de Parc-Extension. 2020. « MIL façons de se faire évincer : L’Université de Montréal et la gentrification à Parc-Extension ». https://antievictionmontreal.org/fr/2020-report-the-university-of-montreal-and-gentrification-in-park-extension/.

Projet LoReLi. 2021. « Pour contrer la pauvreté et l’insécurité des femmes marginalisées et de leurs familles : un soutien adéquat au logement social et abordable ». Présenté à mémoire déposé au ministre des Finances du Québec dans le cadre des consultations prébudgétaires 2021-2022, janvier. https://bit.ly/3raTKJS.

RBQ. 2021. « L’accessibilité aux bâtiments pour les personnes handicapées ». Régie du bâtiment du Québec. 2021. https://bit.ly/3104PCw.

Savard, Andrée. 2018. « Les projets d’habitation pour femmes monoparentales : Des initiatives structurantes à consolider et à développer pour contribuer à l’autonomie des femmes ». Comité consultatif Femmes en développement de la main-d’œuvre. https://ccfemme.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/ccf-avis_meres-monoparentales-et-projets-dhabitation_mars-2018.pdf.

SCHL. 2020. « Enquête sur les logements locatifs : Montréal ». Société canadienne d’hypothèque et de logement. https://bit.ly/3I4Ersu.

———. 2021. « Le marché sous la loupe: RMR de Montréal ». Société canadienne d’hypothèque et de logement. https://bit.ly/3FR7NZ8.

SHQ. 2021. « Modalités administratives 2021-2022 : Programme de supplément au loyer d’urgence et de subvention aux municipalités Volet 1 – Supplément au loyer ». Société d’habitation du Québec. https://bit.ly/32tlOxT.

Statistique Canada. 2021. « Revenu des particuliers selon le groupe d’âge, le sexe et la source de revenu, Canada, provinces et certaines régions métropolitaines de recensement ». Tableau 11-10-0239-01. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/fr/tv.action?pid=1110023901.

TAL. 2020. « Le calcul de l’augmentation des loyers en 2020 ». Tribunal administratif du logement. 22 janvier 2020. https://www.tal.gouv.qc.ca/fr/actualites/le-calcul-de-l-augmentation-des-loyers-en-2020.

Ville de Montréal. 2016. « Portrait des logements accessibles et adaptés dans le parc de logements sociaux et communautaires de l’agglomération de Montréal ». https://bit.ly/3HTVdub.

———. 2020. « Programme d’adaptation de domicile pour personnes en situation de handicap - Un programme bonifié et mieux adapté aux besoins montréalais ». Cabinet de la mairesse et du comité exécutif. 20 février 2020. https://bit.ly/3cR6EEx.

———. 2021. « Période de renouvellement des baux - La Ville de Montréal rappelle certaines règles de protection aux locataires ». 2 mars 2021. https://bit.ly/3cQf536.